Selecting appropriate materials is a key step in the design and construction of buildings and infrastructure. Many considerations are involved in deciding what materials to select, including cost, performance, preference, and availability. In addition, materials substitutions sometimes occur during the construction phase. At times, these selection and substitution decisions have unintended consequences for performance.

In this webinar, materials scientists Jeff Plumridge and Kimberly Steiner, and materials engineer Elizabeth Wagner examine common issues related to materials selection. Three material types are discussed in detail, germane to a range of architectural, structural, and fire protection applications. Reasons for selection or substitution and the unintended consequences of those decisions are highlighted. Finally, important points to consider when selecting materials or requesting or evaluating substitutions are discussed.

more to learn

View this webinar in our interactive audience console to earn 1 AIA learning unit, access related resources, submit questions to the presenters, and download a certificate of completion.

Kimberly A. Steiner, Principal and Unit Manager

Elizabeth I. Wagner, Senior Associate

LIZ PIMPER

Hello everyone and welcome to today's WJE Webinar, Material Selection, Substitution, and Unintended Consequences. My name is Liz Pimper and I'll be your moderator. During the next hour, material scientist Jeff Plumridge and Kimberly Steiner and materials engineer Elizabeth Wagner will examine common issues related to material selection. Three material types will be discussed in detail, germane to a range of architectural, structural and fire protection applications. Reasons for selection or substitution and the unintended consequences of those decisions will be highlighted. This presentation is copyrighted by Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates. And now I will turn it over to Elizabeth to get us started. Elizabeth.

ELIZABETH WAGNER

Thanks Liz and welcome everyone to our presentation on Material Selection, Product Substitutions, and Unintended Consequences. Over the course of the next hour, we'll be talking about different opportunities and challenges that have arisen due to material substitutions and material selection. And we hope that by the end of this presentation, those of you in the audience will be able to identify parameters involved in material selection, describe reasons why materials may be selected or substituted on a project, explore potential consequences of material substitution, and explain reasons that performance may differ from that originally anticipated.

So before we begin with the case studies for this presentation, we want to make sure that everyone's all on the same page with what we're talking about. And so materials selection is one of the key parameters that we'll be discussing today. And so everything that's constructed is made of materials. And any material that's used in the construction process is going to be selected by somebody. Unless somebody could be an architect, an engineer, a specifier, or a contractor, there's a lot of different reasons why materials may be specified.

The decisions about which materials are selected during a project are going to be made throughout the construction process and over the entire life of the structure. And so they can occur during the design phase, during the construction phase, or during the repair phase. And if they happen during the construction or repair phase, sometimes these are called material substitutions.

Issues that you might want to consider when selecting materials are typically going to be cost. How expensive is the material to the project, as well as the performance of the material. Its strength, its durability and its appearance. But some of the less common factors that tend to result in some of the issues that we're going to be talking about today are related to the constructability, the environmental stability, and the materials interactions that this material may encounter in service.

And so with constructability, what we're talking about is the ability for a material to be used with current practices or well-defined modified practices. For environmental stability, we're talking about the ability for the material to remain in its as-built condition with time and exposure to the environment. And then materials interactions, we're talking about the propensity for that material to interact with surrounding and adjacent materials that it may come into contact with in service.

Now, materials selection considers all of these things. And then during construction we may also see substitutions for materials. And there's a lot of reasons why materials may be substituted. And many of these are similar to the reasons for original material selection and they include things like cost, whether it's a value engineering proposal, for example, a perception that the substituted material will provide superior performance to the originally selected material. There may be concerns about sustainability that lead to different materials selection and substitution. Aesthetics. And also in a lot of cases, the availability of the selected material may necessitate a different material to be substituted.

So today we're going to be sharing three case studies covering a wide range of material applications where material selection and/or material substitution played a role and some unintended consequences that were observed. Now, these projects are not intended to be all encompassing by any means, but they are intended to give some examples and highlight the range of applications where materials substitutions could lead to unintended consequences in practice. And so with that, I'm going to pass things over to Kim to start our case studies.

KIMBERLY STEINER

Thank you, Elizabeth. So I'm going to be talking about primary sealant failure in insulating glass units or IGUs. Now, some of you might not know what an insulating glass unit is. So this is the type of glass unit that is used in common window constructions for exterior windows on residences and office buildings. And the purpose is to have a window that is insulating and retains the heat out or the heat in to retain the thermal performance of the building. There's a photograph of a small IGU, and now you see a couple of schematics showing the key features around the perimeter of the IGU.

So first of all, we have the two panes of glass on either side, and they're separated by a space called the airspace and they're separated by the use of a spacer. The purpose of the spacer is to keep those two panes of glass separated. The spacer is often filled with desiccant. Now a desiccant is a material that absorbs moisture vapor out of the air. So this insulating glass unit needs to be kept dry in that space between those two pieces of glass. Otherwise, if you have moisture vapor coming in, it can condense during times of cooling or heating depending on the temperatures, and it fogs and it leads to instead of being able to see through a nice clear glass window, you're now looking at fog. So the spacer often has desiccant.

The next key feature and the one we're going to talk about quite a bit today is the primary sealant. Now the primary sealant is that little gray bar in our schematic. It's difficult to see in the photo, but it's a thin layer of material that is used during the fabrication process to adhere the spacer to the glass. It also helps to serve as a moisture vapor retarder to again try to limit the amount of moisture vapor that's in between those two glass panes.

And finally, there's a secondary sealant, and that secondary sealant is there to provide structural integrity and attach the two panes of glass to the spacer and to the primary sealant.

So the primary sealant is typically made of a material called polyisobutylene. So what is polyisobutylene? I'm going to get a little bit into the materials chemistry today, but I'm not going to go too deep. But PIB polyisobutylene is a polymer with repeated isobutylene unit. So there's a schematic of what the molecule looks like. And if you imagine, the two ends of that molecule keep going for tens of thousands of repeating units. And polymers are long chain molecules and a lot of their properties are dictated by the length of those polymer chains.

So the key properties of polyisobutylene, first of all, it has very low water vapor permeability to help keep that water vapor from getting into the interior of your IGU. It's tacky, which helps during fabrication of the IGU and it's viscoelastic, so it has properties that aid in fabrication, but when it's applied between the spacer and the glass, ideally it should just stay there with time. It should be basically a solid material.

Now polyisobutylene, PIB by itself is a colorless polymer, but companies, manufacturers add additives to change the properties, and these can include pigments and stabilizers. Today we're going to talk about the difference between black PIB and gray PIB. In that photograph that just popped up, these are two slugs of this PIB polymer material that is ready to be heated to make it more flowable so it can be used in the fabrication process. On the left, you see black PIB. On the right, you see gray PIB, and basically they're just different colors.

So why would you choose black versus gray? And the primary motivation is purely aesthetics. On the left, you see an image of a curtain wall system with typical black PIB. It looks probably like a lot of buildings you've seen where you have that little black frame around each unit of glass. On the right is a building with gray PIB, and it looks a little bit different.

Now, black PIB has been in the market for many decades, and it generally performs very well. Gray PIB became introduced about 15 or so years ago into the market. And with time what was observed is that the gray PIB, depending on the formulation can run down into the IGU space. And you can see a couple of photos here where we have some rundown of the gray PIB where it's no longer present simply between the spacer and the glass, but it's run down into the glass away from the spacer. And as you can imagine, gravity affects it. So the rundown happens on the top portion of the unit primarily.

So when this first started happening, we had some inquiries. We got a variety of samples in our lab to look at why this gray PIB is running down. And in order to figure this out, we had to come up with some hypotheses. What are the possible causes of this rundown? One possibility is contamination. There could be a material either introduced during the manufacturing process or from service from that secondary seal or other ancillary materials that lowers the viscosity of the PIB so that it runs down. Or the PIB polymer can get altered to again reduce the viscosity.

So we did a wide variety of lab testing. I'm not going to go into a lot of details here, but basically we did analysis of the PIB looking at, so-called good versus bad samples. So samples, exhibiting rundown and samples not exhibiting rundown, and looking at the differences between them. And we've found that the molecular weight is one of the key differences.

Now, molecular weight is a way to measure the length of the polymer chain. So again, remember we have these repeating units and they're tens of thousands of repeating units long. And so the longer the chain, the heavier the molecule.

So what we did is we collected some samples and we looked at the rundown portion and compared it to the stationary portion. Now, if you remember what we talked about the fabrication process, there's a bead of PIB that's applied to the glass between the glass and the spacer. So the rundown portion and the stationary portion, they were part of the same material, that same slug of PIB, which was heated and then deposited. So they do represent the originally applied material, but the rundown portion is now running down while the stationary portion has not. So what are some of the differences?

One of the primary differences is in the molecular weight. Now you can see here we looked at, in this case, five buildings, different locations throughout the country, different exposures, different heights of buildings, different exposures of the units, but we saw as much as 95% molecular weight loss in as little as four years. So this takes a very long molecule and it's now a shorter molecule.

And as that molecular weight decreases, the viscosity also decreases and that leads to rundown. So again, we're looking at substituting gray versus black. So this is something that a lot of design professionals decided to do during the design process because they liked the look and they wanted a certain appearance of their building. And so they looked at some data presumably from this PIB, and saw that it had similar vapor transmission properties no matter what the color. Viscosity and other properties related to ease of fabrication were also similar.

But what we found out is that they have different stabilities to light. So here again, you can see our PIB molecule and some formulations of great PIB lacked light stabilizers. So as this material's in service, the sun shines, UV rays come down and they interact with the chemical bonds in the polymer. And that can cause breakdown of that polymer through a mechanism called chain scission. Imagine like you're taking a scissors and just snapping that molecule apart.

But this takes time to manifest. It takes time for the UV exposure to build up. It takes time for the molecular interactions to happen for those chains to break apart.

The other thing as you can imagine it doesn't happen necessarily once per molecule. The little diagram there, it looks like it broke a molecule in half. If the light breaks the molecule in half, you now have a 50% molecular weight reduction. But each little piece can then interact with another photon of light and can break down again and again. So we can end up with, as we saw, up to 95% molecular weight reduction.

Now I'm going to talk a little bit about the PIB formulations, right? So we've had black PIB for decades, and then there's more than one gray PIB formulation on the market, and the formulation is a key to the properties. So as we mentioned, right, the PIB itself is colorless. Additives are added to affect the properties including color.

So with the black PIB, it's loaded with a pigment called carbon black. It's used in a lot of black plastics. It's extremely black. You load up your PIB, it's going to be very dark in color. Now, if you want gray, we all know to get gray, you mix white and black, so you can only add a little bit of black to your gray PIB formulation. Think about the carbon black. It's an excellent light stabilizer. So the black PIB is stabilized in large part due to the pigment that is used.

Now, again, to make the gray, we add a little bit of white. That white is typically titanium dioxide, commonly used white pigment, does provide a little bit of UV stability, but again, it's not the same. And the loading of these stabilizers also affects the durability.

Now, some formulations add other additives that do not contribute to the color, but contribute to the long-term light stability of the PIB polymer.

So while gray PIBs may look the same, visually they may be the same color gray, they don't necessarily perform the same because they're not formulated the same.

So if we go back to our little schematic, again, we're looking sort of at the features, the spacer and the primary and secondary sealant around the perimeter of these IGUs, and they're installed on the building and the sunlight shines, and these light rays come down, and then they just start to interact with the primary sealant. Molecular scission happens, viscosity reduces, the material begins to run down, and all of a sudden, right? Well, not all of a sudden, with time, right, you're looking at a window that looks like this instead of what you're expecting.

So when it comes to selections of materials, right, the PIB, it's an essential function in the IGU. I'm not aware of any IGU fabrication that does not use PIB as a primary sealant. And it comes in multiple colors. And those are primarily an aesthetic issue. People like their building to look a certain way, and they choose their color scheme based in large part on that. But the pigment that makes PIB black is also a light stabilizer and that change in color requires a change in formulation. And just a way to think about this formulation, to add stabilizers into the gray to achieve the same durability as you get from the black pigment in the black PIB.

And exposure to natural light causes this chain scission, which ends up with the rundown of certain formulations of PIB down your window. But years can elapse before failure's apparent.

And some of you might be asking yourself, "I'm not a chemist, I'm not a polymer scientist. How on earth would I even start to think about chain scission and interaction with UV light?" And that's a very good question, and it's not something that most design professionals think about.

But what we think is a good idea is if you're evaluating materials that don't have a long track record, you need to start asking some questions. When things have been used for decades with the same formulation, you have a pretty good idea of what's going to happen if you use the same thing. But if there's something new on the market, you need to ask some questions about how's it going to perform and not just initial performance, but also long-term. And there can be a lot of issues that are affected by compositional and formulation changes that most people just aren't going to think about.

And so one of the good resources is your material supplier. Ask them not just about initial properties, but ask them about durability and what testing have they done to consider the durability.

Another good resource, other professionals, your colleagues, professional societies, publications, to see what experience there has been about a new material. Is there evidence of a track record? Do people have some ideas or some knowledge about how something might perform? And with that, I'm going to turn it over to Jeff to talk about another issue.

JEFFREY PLUMRIDGE

For the second case study we're going to talk about CPVC sprinkler pipes, which is related to material interaction and how a product might be affected by the other things and its surroundings once it's installed.

A little bit of history. Traditionally, steel pipes were utilized in fire sprinkler systems. And on the right you can see kind of a traditional steel pipe preparation where you take your steel pipe, you cut it to size, you put it in a threading machine in order to make your pipes of various lengths to install in your plenum space as you're doing your fire sprinkler. But in the past few decades, we've seen CPVC pipes be selected during the material selection process for new construction due to a variety of factors that we'll get into. But as a result of this selection, we've seen some different issues that occur in these CPVC systems that don't really happen for the steel pipe systems, and that results in leaks that cause costly damage and require an awful lot of time for repair.

So what are these advantages to CPVC pipes? Why are people selecting this in lieu of the traditional steel pipes? Well, there's good thermal and pressure stability. So they make good fire sprinklers. They're easy to construct. So I showed the image on the last slide of the traditional steel pipe that involved adding threads to your steel pipe. Well, with CPVC pipes, you can cut it very easily and you only need solvent cement in order to fit these things in place. So you can actually do that right there at the spot that you're installing it rather than having to set up a space in an area to prepare your pipes. They're corrosion resistant. It doesn't rust. It's made of plastic. So obviously you don't have the oxidative degradation of metal like you might see for steel or copper pipes.

And there are some sustainability claims from the CPVC industry in the amount of energy that's used over the lifetime of the material. There's obviously a lot of push in our industry to address sustainability concerns for some of the materials that we're using.

It's also generally considered highly chemical resistant. You see, we have an asterisk there because of the, I'm going to talk about something in a second, but on the right-hand side, you can see this is a traditional CPVC sprinkler pipe installation. So that orange pipe is our CPVC pipe, and this is in a plenum space above a hallway in a multi-unit residential building. And you can see all those other pipes and wires and other things that are involved in that space. The CPVC gives you some flexibility to move around. You can see particularly that those three 90 degree bends that are there that allow the pipe to get around the big black pipe in the middle that is your gas line.

So in terms of the disadvantages, I just alluded to this, but the CPVC is particularly susceptible to chemical attack from select chemicals, things like dishwashing liquids and cleaners, vegetable oils, synthetic oils, plasticizers and different solvents.

And now you might be saying, "Well, these are fire sprinkler pipes. Why would they be exposed to any of these things? There's just going to be water running through it to put out a fire in the event that it's needed." Well, we've actually seen numerous issues related to exposure of these pipes to some of these things. In fact, CPVC manufacturers provide listings of known compatible and incompatible products, and they're always updating it. It's always changing. The state of the industry is changing information related to different products as product formulations will change. And they also provide some general guidance for types of material. So this isn't something that is unknown in the CPVC pipe industry, but it's something that takes a little bit of digging to understand.

And to get into why this might be such an issue, some of the products that they list include the following. We have pipe clamps, we have pipe tape, waterproofing materials, water additives, water sheathing, dye penetrants, duct sealant, thread sealants, cleaners and disinfectants, mold inhibitors, leak detectors, caulks or sealants, and then fire stopping systems. So all of these things that may be in and around that plenum space and that image that I just showed could be in contact with the CPVC, which causes an issue.

And what is that issue? Well, it's called environmental stress cracking. So I'm going to take a little bit of a dive into the technical side here. But environmental stress cracking the definition of it is that it's a type of fracture or failure of a material, in this case, we have a plastic pipe, that is due to the combination of stress and chemical attack or a chemical agent that's been placed on that CPVC.

And our CPVC pipes are always going to be under stress. You can see on the image on the top, this is a sprinkler pipe installation and it's hanging from a hanger. And those hangers often cause a little bit of flexural stresses to be placed on the pipe. In addition, these pipes are under pressure. And so we have the water pressure, what we call hoop stress, that is shown on the image in the bottom left that is always pushing out on the plastic.

So these pipes are always under stress. And generally without these bad chemical actors, those pipes are going to be perfectly fine. The amount of stress that they're under is not enough to cause any sort of failure. But when you add this chemical environmental stress cracking agent to the pipe, then you start to get failures. And you might be asking, what do these failures look like? Well, here's some examples. Here's a pipe that's been put in contact with some wiring.

The wiring has plasticizers in the sheathing, and what can happen there is that we get the formation of cracks on the outside of the pipe. You can see there they're indicated by the arrows here.

We also see an awful lot of cases where you have your caulk or your sealant that is put around the pipe as the pipe goes through wall penetration. And that caulk or sealant is not approved for use with CPVC pipe. Like I said, there are listings that tell you which caulks can be used with CPVC and which ones shouldn't be. In this case, this pipe was not supposed to be used with CPVC pipe. And I'm cheating a little bit. This pipe isn't a fire sprinkler pipe. It's a pipe for domestic water, but they undergo the same sort of failure. And you can see on the top of the image we have that white sealant that's circling around the pipe. Once it's removed, you can see underneath on the image on the bottom right, it's been fully discolored indicating this chemical attack is happening.

Sometimes in extreme cases it might cause actual damage and bulging of the pipe when you add these incompatible chemicals. It can cause circumferential cracks like we see in the bottom right, and it can cause cracks that obviously start on the outside and work all their way to the inside. You can see this image here. This is the interior of the pipe that I showed on the previous slide. So the cracks have started on the outside of the pipe and they work their way all the way to the interior.

So what is actually happening? Well, the plastic is softening, and as the plastic softens, it can't hold the same amount of stress. This is what it looks like when we look at the fracture surface of the crack. It softens and it very easily kind of cleaves open. We see it here for this image of the circumferential crack. You can see on the top of the image that it's very, very smooth. It almost looks like it was cut by a very slow blade as opposed to fracturing and cracking open. And the incompatible chemicals are what caused that to happen. It allows it to have this very smooth fracture formation.

And you can see here this is evidence of some of this chemical attack. So here's a cross section of the pipe that I showed on an earlier image, and what's happened is that this incompatible material has penetrated into the CPVC and it caused the CPVC to swell. And so the circle shows the original size of the CPVC, and with the sealant that was applied, starting from the locations of these arrows, it has caused that pipe to swell. And because that material is swollen, you could actually scrape it off with your fingernail. So your CPVC instead of being hardened and durable, is now very soft, which means that it can't withstand the same pressures or stresses that it could have previously.

We also see some interior exposure issues where someone might've introduced some sort of anti-freeze type of agent that is incompatible with CPVC that can cause fractures from the interior.

So when it comes to the material selection issues for CPVC, there's some very obvious advantages. It's easy to assemble. It's lightweight. Instead of lugging around steel pipes, you can carry these plastic pipes and you can kind of put them together and assemble them right in place. There's no rusting, pitting, or corrosion of the material. They have some sustainability benefits. They're really suitable for these fire sprinkler piping.

The disadvantage is that, yeah, they have these environmental stress-cracking concerns, and the stress conditions may be non-uniform. In some cases there might be a lot of stress. In some cases, there might be a little bit of stress all in the same system depending on how it's installed. So you might get sporadic breaks in places where there's a lot of stress and in other locations it's perfectly fine. And the chemical exposure may be intermittent. There might be floors where somebody has used the wrong sealant in your building and floors where somebody used the right sealant and only the floors with the wrong sealant are ever going to have issues. So it can be very frustrating for building owners.

The exposure to common materials of construction can cause failures. And these failures unfortunately don't happen immediately. They happen months to years after installation. So it's something that people are dealing with five, six, seven years after their pipes have been installed. And really what it comes down to is that care is required when specifying and installing nearby materials. It's not that these things don't have a proven track record of use. It's that there are other things that can happen to the pipes after they've been installed that can cause some issues.

And so when it comes to these material selection issues, particularly related to material interaction, you have to be sure to consult the up-to-date manufacturer recommendations. If you were to look 10 years ago at what CPVC manufacturers might be saying you could use with your pipes and use around your pipes, that will have changed year by year. And so people really need to keep up to date with what current recommendations are that are put out by the industry.

The other is that you have to communicate with the project team to make them aware of differences in the requirements for specified or substituted materials. Your pipe installer very likely understands the issues related to CPVC pipe and will attempt to avoid them. But other folks who might be working in the same area, you saw how crowded that plenum space was in the image that I showed, they might not understand that there are issues related to chemical incompatibilities of other things that are in there. And so that has to be communicated across the board to the various folks who might be working in and around this installation. So it's a bit of a change in communication and a change in understanding.

And from there, I'm going to pass it off to colleague Elizabeth Wagner to discuss our final case study.

ELIZABETH WAGNER

All right, thanks Jeff. So for our last case study, I'm going to talk about some cementitious material substitutions, which are really becoming more of a challenge that we're seeing in recent years.

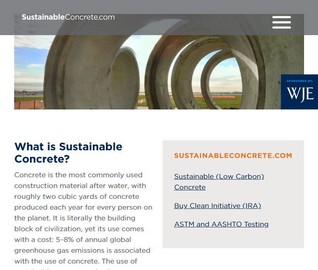

So for those of you who don't work in the world of concrete, concrete is the most widely used building material in the world, and its typical components include cementitious materials, water, coarse and fine aggregates which are rocks and sand, and some chemical admixtures that can be used to tailor the performance of the concrete.

The cementitious materials, and by cementitious materials right now I'm talking about primarily Portland cement makes up about 15 to 20% of the volume of the concrete. And that will react with water to give the concrete its strength giving properties, its durability and so on. Recently we've seen issues arise or not necessarily issues arise, but an increased drive for substituting cementitious materials driven by the large CO2 emissions that are associated with the production of Portland cement.

Portland cement has been estimated to account for about 5 to 8% of all global CO2 emissions each year. And 85% of those emissions are coming from what's called the clinkering process, which is used to create Portland cement, clinker, or nodules of Portland cement that get ground into a powder. This is produced from feedstock materials. And so let's take a look at the process really quickly to see where those CO2 emissions are coming from.

So on the left of this image, I'm showing a clinkering process. You've got raw materials entering on the left side. And they're heated up to very high temperatures in the kiln. Now because they're high temperatures, there's a lot of fuel combustion involved. And the fuel combustion alone, depending on the feedstock of the material that's used for the fuel generation at the particular plant, that can emit up to a half a ton of CO2 for each ton of clinker that's produced.

Once these raw materials are heated up very high, they turn into a molten material that gets fused together and becomes the clinker that ultimately becomes the Portland cement. And one of the feedstock materials that is doing this is limestone. And so when limestone is heated up, it's the process, we call it calcining. When limestone is heated up, it decomposes and as just a chemical byproduct of that, it emits CO2 into the air. And so that's another roughly half ton of CO2 that's produced for each ton of clinker that's being produced.

So that's a lot of CO2 from a single process. And so with an increased focus on sustainability in recent years, there's been a push to reduce Portland cement usage in our construction processes to help reduce some of the associated CO2 emissions.

So how do we reduce Portland cement usage? There's three primary ways. The first way, which is what we've been doing for decades, is to substitute a portion of the Portland cement that's in the concrete with a supplementary cementitious material or an SCM. Some of these materials are byproducts from other manufacturing processes, and so they're considered even better from an environmental sustainability perspective because you're reusing byproduct materials that would otherwise be waste. And so things like fly ash and slag cement are used in these ways. There's other naturally occurring materials like natural pozzolans, and then we've got materials like silica fume that can be manufactured as well to create very good properties for our concrete.

The impact of these specific materials is going to vary depending on the material. Their impacts on both fresh and hardened properties of the concrete will depend primarily on the chemical composition and the physical particle size, as well as the particle shape or morphology of these SCMs.

Another way of reducing Portland cement usage, which is becoming increasingly more common over the last few years, is to substitute a portion of the Portland cement itself with another material. And this is what gave rise to blended cements, which are covered by ASTM C595 or AASHTO M 240. Now in these standards there are two different types of blended cements or broad categories. One is blends of cements with SCMs, and these are just like what we saw in the previous slide, but these happen at the cement manufacturing level, and these types of cements are called Type 1P, Type 1S, Type 1T, and so on, depending on which specific SCM and combination is substituted.

In more recent years we've seen a rise in what's called Portland limestone cements or Type 1L cements. And in these cements between about 5 and 15% of our Portland cement clinker is now substituted with an inter-ground limestone powder.

And the impact of this limestone powder substitution, just like we saw with the SCMs, is going to depend on the type of limestone, the composition of the limestone, its substitution rate in our cement, and as well as the particle size distribution of our blended cement.

The third way to reduce Portland cement usage, and I'm not going to go into too much detail on this one, but this is to replace Portland cement with an alternative cement. And I put cement in quotation marks because it's really a different binder for our concrete, a different material that's given concrete its strength and hardened properties than what we might be used to with these Portland cement systems. And there's a lot of materials that are available and currently under development. This is a very rapidly developing area. There's calcium aluminate cements, calcium sulfoaluminate cements, alkali activated materials, which are also called geo polymers. There's limestone calcine clay cements or LC3s. And all of these materials are going to have different impacts on the fresh and hardened properties of concrete, which depend on the chemistry of the specific alternative material, as well as its particle size distribution.

So I'm going to turn back my focus now to the Portland limestone cements. The PLCs or Type 1L cements. And the reason I'm focusing on this is because these are quickly becoming the dominant cement type in most US markets today. When they were first approved for use in the United States back in 2012, they made up less than 5% of the market share, and currently they're over 60% of the market share just 12 years later nationwide. And in many markets, including our Chicago land market here, they can be the only cement type that's available.

Now because it has been so quickly adopted, people are having a little bit more challenges with the substitution of what they used to be using a Type 1 cement or a Type 2 cement or a Type 5 cement. These Portland cements when they're substituting the Type 1L cements, there's challenges that people are reporting, whether that be lower strength or slower strength development, challenges with finishing, which is what I'm showing in this picture here, higher plastic shrinkage tracking, higher air contents. There's been a lot of challenges that have been reported, and the question needs to be asked, is the Type 1L cement responsible for these challenges?

In some cases, probably yes. In other cases, probably no. But we're going to take a look really quickly to see how these materials work to see what their effects could be and where some of these issues may originate from.

So this is my most technical slide here. This is a schematic illustration of Portland cement hydration. So we have our unhydrated cement powder on the left. It's got a bunch of different chemical phases that when we add water, it reacts or hydrates to form what we call cement paste. And that cement paste is going to have different reaction products, CSH, calcium hydrate, which is, yeah, ettringite monosulfate, different types of reaction products that are going to give the concrete its hardened properties and its durability properties. I'm not going to go into detail about these specific reaction mechanisms, the reaction products that are taking place. I want you to focus mostly on the fact that when we have our Portland cement and water, it hydrates. And so if we change the chemical and physical properties of our cement, then we should expect a change in the hydration reaction as well.

And so to illustrate this for PLCs, I'm simplifying that illustration from the previous slide, and now we've just got hydrated cement on the left, reacting it with water and creating our hydration product. So our hydration product is the darker gray reaction rims, and the porosity or the space in between these hydrated cement particles is the white gaps in between. If you have a lot of porosity, you tend to have lower strength and less durability is the basic takeaway there.

So if we substitute a portion of our Portland cement clinker with limestone powder like I'm showing here on the left and then react it with water, there's a few things that you can see. The first is what we call a dilution effect. If there's less Portland cement there, then in certain concrete mixtures we can have less hydration product, which would increase porosity, it may decrease strength and so on.

We also have what's called a filler and a nucleation effect, and these are coupled effects. So if you have a broader particle size distribution because you've got these limestone particles hanging out in your system, you get improved particle packing, which can improve hydration and in some cases reduce porosity.

We also have a higher surface area. A higher surface area means that you have faster early reaction rates, but it also means that you need more water for your concrete. And because you need more water or you could need more water, it may change the way that that water manifests on the surface. And we call this bleed. And bleed is really important for concrete finishing operations, which is where we're seeing a lot of the challenges with the use of PLC substitutions.

So if we have a substitution of PLC and we don't make any adjustments to the concrete mixture designs or to the concrete practices, it can lead to unintended performance impacts. And so like I've been saying, one of the areas where we see a lot of challenges is in finishing concrete slabs. Normally when concrete slabs are being finished, there's a lot of history here and a lot of empirical evidence that is used to determine when is the appropriate time to start finishing the slab. And a lot of people will finish slabs based on visual appearance of the slab. When does the bleed water disappear? When does the concrete get shiny and then lose its sheen? And that dictates when a lot of people start finishing the slab.

But because the Type 1L cements, these Portland limestone cements have different and altered rates of bleed, that timing can get thrown off if you're just using visual indicators. And if your timing is off, it could lead to delaminations because you're trapping some of that bleed water under the surface and it leads to some water that can get trapped under the surface and cause this scaling to happen.

So some of the key takeaways here is we can't substitute materials, cementitious materials at least one for one without making adjustments to the mix design. And we can't always rely upon this empirical knowledge that we've developed based on the performance of past concrete mixtures.

So just to summarize high level, again, our cementitious material substitution issues that we're seeing are largely driven by sustainability concerns. It's not that there's an issue because of sustainability. It's that we're seeing more substitutions of materials driven by sustainability. And the performance can be affected when we change things like particle size, particle shape, composition. And if we're not careful, that can lead to some of these unintended consequences that we're seeing.

It takes a lot of time to understand the variety of effects that these new materials can have on performance and changes in cementitious materials may need to change the way that we think about how we do concrete, how we proportion the concrete mixtures, how we install it in practice, and so on.

And so laboratory trials, field trials and mock-ups are really useful tools to helping improve awareness and understanding of the construction and performance-related challenges that we may encounter when we have these materials substitutions.

And before I finish up and pass things back to Jeff, I just want to highlight in the resources section on your display, there's a link to some low-carbon or sustainable concrete website where we have a mock-up of an actual low-carbon concrete trial that was recently performed to help raise awareness of some of the challenges and improve our understanding of these construction-related performance challenges. So with that, I'm passing things back to Jeff.

JEFFREY PLUMRIDGE

Thank you Elizabeth. So just a brief summary of some of the things we've discussed today, as well as a couple of questions to be considered when we're talking about material selection or substitution. Is a material compatible with its environment? Are adjacent materials compatible with each other? Is there a track record of similar use? Has the material formulation changed since last use? That can be very tricky to figure out. Does the project team understand how to properly account for a change in material as Elizabeth just showed? Have manufacturer's advisories been reviewed?

There can be advantages obviously with using newer materials compared to existing materials and doing substitutions during the selection process. But the important thing and the takeaway we hope that you take is that they are not the same and will not necessarily behave the same. These differences in performance, there are good and bad differences need to be considered as part of the selection or substitution process.

And just to summarize what we talked about at the beginning, during the material selection process, we obviously are considering the desired performance of the material and obviously the cost. There's a balance between those two things. But digging a little bit deeper, we have to consider the constructability, the environmental stability and the material interaction.

For material substitution, there are a variety of different reasons that are listed there, why this can happen, why we might want to do or need to do a material substitution. But material substitution it's just material that occurs later on in the construction process. So you really have to account for all of those same things that we have listed in the first bullet point for the material selection as part of your material substitution process.

Now, there are an awful lot of resources that you can turn to in order to aid in your material selection. There are designed professionals. There's a lot of published literature from a variety of different organizations. The material manufacturers do provide a lot of good information related to how to use their product, what not to do when using their product in particular.

Professional societies are doing an awful lot of work, especially related to things like the Type 1L cements in order to try to figure out how we need to change how we approach the placement of concrete. There are a variety of decision-making tools that are available online or through different parties. Mockups are always a very good idea. So if you have a new material and you want to see how it might perform, particularly if you have a long construction process, you can do a mockup very early and just see what it does, see if there are any issues that arise that you can then account for in your placement of that material.

And then laboratory testing. Using a laboratory or a trusted group to assess a material to see how it might be performing when it's selected or substituted for something that you know as a performance that you can trust.

And with that, we've reached the end of our webinar. We very much appreciate your attendance and we are going to open things up to questions.

LIZ PIMPER

All right, thank you Jeff, and thanks Elizabeth and Kim for the great presentation. So our first question's really two questions that are related. I'll read them both, kind of general to the three of you and to your case studies. Why doesn't ASTM testing pick up on these issues before the product is certified for use? And are new ASTM tests needed to cover performance issues in these newer materials? Is testing lagging material innovations?

KIMBERLY STEINER

Well, Liz, I'll take a stab at this. ASTM tests are, first of all, it's a consensus organization, so there's a variety of people who make the test methods and who decide what should be considered. And some of those people may not be aware of some of these degradation mechanisms, and at times somebody might not want to have a test that is overly rigorous or too expensive to execute. So it's very difficult to anticipate a test method that is comprehensive enough to evaluate unintended consequences yet practical enough to actually get used. But ASTM methods are being evaluated constantly. There are typically meetings twice a year to look at existing methods and standards, and it just takes some time to get a new method on the books though.

ELIZABETH WAGNER

I'll also add on the topic of cementitious materials and ASTM standards because the Portland limestone cement have becomes the only cements available in certain markets, ASTM is actually revising a lot of standards to allow for the use of those materials for other types of properties that are being evaluated. So it's a very interesting time to be looking at testing and testing evolution.

LIZ PIMPER

Okay, thanks. So this next question is specifically about the first case study. So Kim, what is the best way to catch a substitution you don't want between gray PIB and black PIB of it to know which manufacturer it is or will the colors be obvious in the submittals or do you just write the specifications to ban the gray PIB?

KIMBERLY STEINER

Well, writing a good quality specification can solve a lot of problems downstream. If you know exactly what you want, then I would suggest writing your specification to be exactly what you want. You can also write specifications to include or exclude certain materials, and for that you have to have a knowledge, not just of color potentially, but of manufacturer or product name.

And the other thing of course, is often a design professional will have to sign off on submittals, so look at what's included in the submittal and make sure that if you're being asked to sign off on it, that you agree and your questions get answered.

LIZ PIMPER

Okay. Another question for you, Kim. Did the gray PIB fail on both the exposed and interior faces of the IGU?

KIMBERLY STEINER

Sometimes yes, and it depends a lot on the local conditions on what the building looks like, where it faces, how shaded it is, what the sun is doing, but sometimes, yes.

LIZ PIMPER

All right. This is a question for you, Jeff. Do similar problems occur with domestic water piping, which can also be exposed to deleterious chemicals?

JEFFREY PLUMRIDGE

The answer is yes. I'll say that CPVC is used probably more rarely in domestic water piping than in fire sprinkler type systems. It is used, but it doesn't have the same sort of market share in the same way that it might have in the fire sprinkler space.

You see a lot more copper piping or PEX piping perhaps in domestic water systems. CPVC will have the same sort of issues. It is installed in the same fashion and there isn't any sort of treatment that can make it less susceptible to these issues. In fact, we often see it's exacerbated in domestic water systems, especially hot water systems, because the heat can actually cause this phenomenon, this environmental stress cracking to happen more quickly. So the failures actually happen more rapidly in the domestic systems. So the answer is yes, CPVC is susceptible no matter the type of installation.

LIZ PIMPER

Okay. Another question for you, Jeff. The ESC appeared to result in cracking and a brittle type failure in the early examples. For examples where the CPVC softened and bulged, is there a different mechanism acting on the material?

JEFFREY PLUMRIDGE

Yes, that's a very good question. And in fact, the image that I showed is something that we're currently looking at. So that pipe is a pipe that we have in our laboratory right now. It's the same sort of mechanism in the sense that the plasticizer from the cylinder caulking is acting on the CPVC, making it embrittled. In that case it was the cylinder caulk is a lot stiffer than kind of the traditional cylinder caulk we might see, which kind of caused the pipe to almost act like a pressure vessel. And so it slowly blew up think of like a balloon before it actually fractured. It's a really interesting one. My colleagues, I had to show them that pipe sample when it came in because it was kind of unique to some of the failures we've seen.

LIZ PIMPER

All right, thanks Jeff. This one's for Elizabeth. How does cementitious substitutions affect use of wet curing versus curing compounds and types of curing compounds?

ELIZABETH WAGNER

Yeah, so this is a good question. We've actually seen this over the last several decades going back as far as some of the substitutions with supplementary cementitious materials. And certain substitutions in the world of concrete require essentially more moisture to be provided during curing. Curing compounds themselves are primarily most effective if you have some amount of bleed water that can rise to the surface because that is the mechanism that it's using to seal in some of that water and help maintain some of the moist environment.

And so if you have a substitution that bleeds less or a material that just has a higher water demand, then curing compounds may or may not be as effective, and use of traditional wet curing methods applying sprinklers or wet burlap or something like that may be more efficient and may even be necessary for certain concrete mixtures with these newer substitutions.

LIZ PIMPER

All right. I've got time for one more question. This is a more general question. I represent design firms and often we get into fights over the level of detail the designer should know versus the product manufacturer versus the contractor. Should the manufacturer be invited into the project team early to consider how the product is going to be used?

KIMBERLY STEINER

Well, I think getting as much knowledge as you can early in the process is helpful to having a better outcome. It can get very tricky with what everyone knows and what people are expected to know, and I certainly understand that. But I think getting your resources available to you sooner rather than later is more likely to keep the process running smoothly.

ELIZABETH WAGNER

And if you're using proprietary systems in particular, I think the manufacturer is a key resource in the process of understanding how the material is going to be used and installed.

LIZ PIMPER

All right. Well, thanks Elizabeth. Thank you, Kim and Jeff. That is all the time that we have for questions today. Thank you for joining us. We hope it's been educational. So again, thank you so much for your time and we hope you have a great rest of the day.

RELATED INFORMATION

-

WJE's Janney Technical Center (JTC) provides advanced testing and forensic capabilities to... MORE >Labs | Janney Technical Center

WJE's Janney Technical Center (JTC) provides advanced testing and forensic capabilities to... MORE >Labs | Janney Technical Center -

Jeffrey Plumridge, Senior AssociateWJE Northbrook MORE >People | Jeffrey Plumridge, Senior Associate

Jeffrey Plumridge, Senior AssociateWJE Northbrook MORE >People | Jeffrey Plumridge, Senior Associate -

Kimberly A. Steiner, Principal and Unit ManagerWJE Northbrook MORE >People | Kimberly A. Steiner, Principal and Unit Manager

Kimberly A. Steiner, Principal and Unit ManagerWJE Northbrook MORE >People | Kimberly A. Steiner, Principal and Unit Manager -

Elizabeth I. Wagner, Senior AssociateWJE Northbrook MORE >People | Elizabeth I. Wagner, Senior Associate

Elizabeth I. Wagner, Senior AssociateWJE Northbrook MORE >People | Elizabeth I. Wagner, Senior Associate